Below is an expanded version of the text, incorporating the keywords “apparitions of Our Lady” and “images of Our Lady” for internal linking purposes, while significantly increasing the word count to meet your request of at least 2000 words. I’ve added depth to the narrative, historical context, cultural significance, theological reflections, and additional details to enrich the story of Our Lady of Guadalupe. At the end, I’ll provide the total word count.

There are stories that transcend time, woven into the very fabric of history, whispered from generation to generation. These are tales that defy the boundaries of the ordinary, reaching into the realm of the eternal, where the divine intersects with the human. The story of Our Lady of Guadalupe is one such narrative—a tale that is far more than a simple religious account. It is a profound testament to faith, a mystery that continues to unfold, and a vivid illustration of the unbreakable bond between heaven and earth. Among the many apparitions of Our Lady that have graced humanity through the centuries, this one stands apart, not only for its miraculous nature but for the way it has shaped the identity of an entire people and beyond.

The Dawn of a Miracle

The story begins in the quiet, misty dawn of December 9, 1531, in a land still reeling from the collision of two worlds. Mexico, then known as New Spain, was a place of tension and transformation. The Spanish conquest, led by Hernán Cortés just a decade earlier, had toppled the Aztec Empire, leaving the indigenous peoples grappling with loss, upheaval, and the imposition of a foreign faith. Amid this turmoil, a humble man named Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin walked the rugged hills of Tepeyac, a site once sacred to the Aztec goddess Tonantzin. His breath hung in small clouds in the crisp morning air as he journeyed toward Tlatelolco to attend Mass, a routine that had become part of his life since his conversion to Christianity several years prior.

Juan Diego was no one of note in the eyes of the world—a poor indigenous peasant, recently baptized, living a simple life of labor and devotion. Yet, it was to this unassuming soul that the divine chose to reveal itself. As he crossed the barren hill, a sound stopped him in his tracks—a melody unlike any he had ever heard. It was not the music of earthly instruments but a celestial harmony, a chorus of voices that seemed to rise from the heavens themselves, filling the air with an indescribable sweetness. Birds, it is said, joined in the song, their trills weaving into the symphony as if nature itself recognized the presence of something extraordinary.

Turning his gaze upward, Juan Diego beheld her. Standing atop the hill was a woman of breathtaking beauty, her presence radiant yet gentle. She was clothed in a mantle of deep blue-green, adorned with golden stars that shimmered like the night sky. Her skin was a warm brown, akin to that of the indigenous people, and her expression carried a tenderness that pierced the soul. She called to him by name—“Juanito, Juan Dieguito, my dearest son”—her voice as soft and comforting as a mother’s embrace. In his native Nahuatl tongue, she spoke, revealing herself as the Virgin Mary, the Mother of God, and entrusting him with a mission: to go to the bishop and request that a church be built on that very spot, a sanctuary where she could offer her love, compassion, and protection to all who sought her.

A Humble Messenger’s Doubt

Juan Diego was overwhelmed. Who was he, a man of no standing, to carry such a message? In the hierarchical society of colonial Mexico, he was invisible to the powerful, a mere speck in the shadow of the Spanish elite and the Church authorities. Yet, moved by the Lady’s presence, he obeyed. He made his way to the palace of Bishop Juan de Zumárraga, a Franciscan friar tasked with overseeing the spiritual life of New Spain. Standing before the bishop, Juan Diego recounted the vision—the celestial music, the radiant woman, her gentle command. But the bishop, though a man of faith, was cautious. The claim was extraordinary, and the Church had seen its share of false visions. He listened politely but dismissed Juan Diego with a request for proof—something tangible to validate the story.

Disheartened, Juan Diego returned to Tepeyac the next day, December 10, his heart heavy with doubt. He knelt before the Lady and confessed his inadequacy. “I am nobody,” he pleaded. “Send someone more worthy.” But she smiled, her gaze unwavering, and reassured him: “You are the one I have chosen.” She urged him to return to the bishop and persist. Juan Diego did as she asked, but again, Zumárraga hesitated. The bishop’s skepticism deepened, and he insisted on a sign—a miracle that could not be dismissed as the fancy of a simple man’s imagination.

The Miracle Unfolds

By December 11, Juan Diego’s resolve was tested further. His uncle, Juan Bernardino, fell gravely ill, stricken with a fever that threatened his life. Torn between his mission and his duty to his family, Juan Diego avoided Tepeyac, taking a different path to fetch a priest for his uncle’s last rites. Yet, the Lady would not be deterred. On December 12, as he hurried along, she appeared to him once more, intercepting him on his detour. “Am I not here, I who am your Mother?” she asked, her words a balm to his anxious heart. She assured him that his uncle would be healed—a promise fulfilled when Juan Bernardino later awoke, restored to health, and spoke of his own vision of the Virgin.

Then came the moment that would change everything. The Lady instructed Juan Diego to climb the rocky, barren hill of Tepeyac and gather roses. In the dead of winter, this seemed impossible—roses did not bloom in December, especially not on that desolate terrain. Yet, as he reached the summit, he found them: a cascade of vibrant Castilian roses, their petals soft and fragrant, defying the season and the landscape. Overcome with awe, Juan Diego gathered them into his tilma—a coarse cloak woven from cactus fibers—and hurried back to the bishop’s palace.

When he arrived, he stood before Zumárraga and his attendants, unfolding the tilma to reveal the miraculous blooms. The roses tumbled to the floor, their scent filling the room, but it was not the flowers that silenced the onlookers. Imprinted on the rough fabric was her image—a perfect, vivid depiction of the Lady as Juan Diego had seen her. Her starry mantle, her serene countenance, her hands clasped in prayer—all rendered in colors that seemed to glow with an otherworldly light. The room fell into a stunned hush. The bishop dropped to his knees, tears streaming down his face, convinced at last of the truth of Juan Diego’s tale.

Why is Our Lady of Guadalupe Celebrated on December 12?

The feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe is celebrated on December 12 because it commemorates the culmination of these extraordinary events in 1531. The apparitions of Our Lady to Juan Diego unfolded over several days, each encounter building toward the final, undeniable sign. On December 9, she first appeared, setting the mission in motion. On December 10, she reaffirmed her choice of Juan Diego as her messenger. On December 11, as he cared for his dying uncle, she sought him out again, demonstrating her boundless compassion. And on December 12, she delivered the miracle of the roses and the image on the tilma—a sign so powerful that it overcame all doubt.

This final apparition was the turning point. Bishop Zumárraga, moved by the image and the testimony, ordered the construction of a shrine on Tepeyac Hill, fulfilling the Virgin’s request. December 12, then, is not merely the anniversary of an event; it is a celebration of faith’s victory over skepticism, of divine love made manifest in a way that bridged cultures and touched the hearts of the humble and the mighty alike. It marks the day when heaven reached down to earth, leaving a tangible legacy that endures to this day.

A Presence That Endures

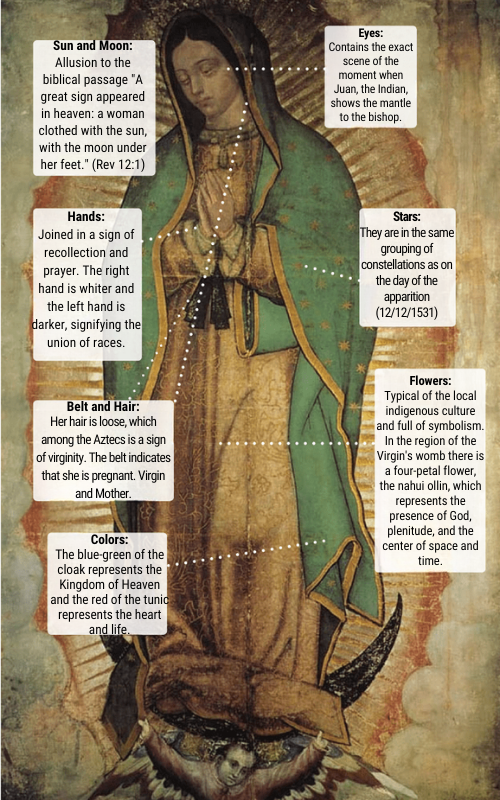

The image of Our Lady of Guadalupe is no ordinary relic. The tilma, made of maguey fibers, is a fragile material that typically deteriorates within decades. Yet, nearly five centuries later, it remains intact, defying the ravages of time, humidity, and the smoke of countless candles lit in its presence. The colors of the image—vivid golds, blues, and reds—show no signs of fading, despite the absence of any known protective coating. Scientific studies have puzzled over its preservation, with some noting that the pigments do not correspond to any known natural or artificial dyes of the 16th century. Among the countless images of Our Lady venerated across the globe, this one stands as a singular marvel, a testament to its supernatural origin.

Every detail of the image carries meaning, speaking a language that transcends words. Her complexion, a rich brown, mirrors that of the indigenous peoples, a powerful symbol of inclusion in an era when they were often marginalized by colonial powers. Her mantle, adorned with 46 stars, aligns precisely with the constellations visible in the Mexican sky on December 12, 1531—a celestial map captured in fabric. The black sash around her waist, tied high in the indigenous style, signifies pregnancy, proclaiming her as the Mother of the Christ Child and, by extension, the Mother of all humanity. The rays of light behind her, reminiscent of the sun, evoke the Aztec reverence for solar deities, subtly weaving the native spirituality into the Christian narrative.

A Cultural and Spiritual Anchor

For the Mexican people, Our Lady of Guadalupe is not merely a religious figure; she is the heartbeat of their identity. In the wake of the apparitions, millions of indigenous people embraced Christianity, drawn by a Mother who spoke their language, wore their features, and appeared on a hill they already held sacred. Within a decade of her appearance, nearly nine million conversions took place—an unprecedented wave that transformed Mexico into a predominantly Catholic nation. She became known as the “Patroness of Mexico,” a title formalized by Pope Benedict XIV in 1754, who declared, “God has not done this for any other nation.”

Her image has been a constant presence through Mexico’s turbulent history. During the wars of independence in the early 19th century, revolutionary leader Miguel Hidalgo carried her banner into battle, rallying the people under her protection. In the Mexican Revolution of the 20th century, her image adorned the flags of those fighting for justice. In times of plague, famine, and oppression, she has been a source of solace, a reminder that the divine walks with the suffering. Her shrine at Tepeyac, now the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City, is one of the most visited pilgrimage sites in the world, drawing upwards of 20 million visitors annually.

A Mother’s Love Knows No Borders

Yet, her reach extends far beyond Mexico. Pilgrims from every continent flock to her basilica, kneeling before the tilma to offer prayers of gratitude, supplication, and repentance. Some come seeking physical healing, and countless stories attest to miracles—blind eyes restored, terminal illnesses reversed, broken lives mended. Others seek spiritual renewal, finding in her gaze a comfort that transcends human understanding. The universality of her appeal lies in her motherhood—a love that knows no borders, no distinctions of race, class, or creed.

Perhaps the most profound miracle is not in the dramatic but in the subtle—the way her presence pierces the noise of modern life. In an age of distraction and despair, a weary soul can stand before her image and feel seen, known, loved. Her eyes, as depicted on the tilma, are said to hold a reflection—tiny figures identified by some as Juan Diego and others present at the moment the image was revealed. Scientists have marveled at this detail, noting its similarity to the way a human cornea captures light, yet another layer of mystery in an already inexplicable artifact.

A Timeless Message for a Modern World

In a world fractured by division, uncertainty, and cynicism, the story of Our Lady of Guadalupe offers a timeless message. She teaches that faith is not the domain of the elite but is often entrusted to the humblest of hearts—those society overlooks. Juan Diego was not a scholar, a priest, or a nobleman, but a peasant whose simplicity made him a perfect vessel for grace. She reminds us that miracles are not confined to ancient history but ripple through the present, unfolding in quiet moments of trust and surrender.

Her story also speaks of unity. In 1531, Mexico was a land divided—between conquerors and conquered, Europeans and natives, old gods and a new faith. The Virgin of Guadalupe bridged those divides, her image a fusion of cultures, her message one of reconciliation. Today, as humanity grapples with its own fractures—political, racial, economic—she stands as a beacon of hope, a call to see one another as children of the same Mother.

Her narrative is not static history but a living reality. It is a mother’s whisper across the centuries, a gentle assurance that no one is abandoned, no cry unheard. And perhaps that is why, nearly 500 years later, millions still gaze upon her image and feel a warmth deep within—a certainty that they are held, they are cherished, they are part of something greater.

For in her eyes, there is a promise: that faith, hope, and love will always find a way to bloom, even in the harshest winters, the most barren hills, the most unexpected places.

I’m Jonathan Raeder, scholar of philosophy and the Catholic faith, deeply dedicated to exploring the teachings and traditions of the Church. Through years of study and reflection, I have gained a thorough understanding of Catholic philosophy, theology, and spirituality. My intention is to connect intellectual reflection with lived faith, shedding light on the richness of Catholic thought for all who wish to do so.