Picture a mind vast enough to cradle the cosmos, yet so hushed it barely stirred the air around it—a soul whose quiet scribbles built a towering cathedral of truth that still pierces the sky. That’s Saint Thomas Aquinas, a Dominican friar whose life lit up the medieval gloom like a lantern in a storm. His journey glows with a steady flame: it sparks in a rugged Italian castle, blazes through dusty lecture halls and candlelit cells, and fades in a blaze of divine wonder that left him awestruck. For you, an American Catholic who’s ever wrestled with life’s big questions or sought a steady guide through the fog, come warm your hands by this fire with me. Let’s trace the path of the “Silent Ox,” a Doctor of the Church who tamed Aristotle’s wild philosophy, lifted it to heaven, and glimpsed a God so vast his own brilliance felt like ashes.

The Noble of Roccasecca: A Boy Born to Defy the Odds

Thomas Aquinas came into the world in 1225—no one’s pinned down the exact date—in Roccasecca, a craggy outpost perched between Rome and Naples. His father, Count Landolfo, was a warrior noble with a grip on power; his mother, Theodora, a softer presence who spun faith into their home like thread on a loom. The youngest of seven, Thomas was a chubby, thoughtful kid in a family eyeing him for greatness—not as a knight, but as abbot of Monte Cassino, the ancient Benedictine stronghold nearby. At 5, they shipped him off to its echoing halls, where monks in black robes chanted Psalms and scratched Latin onto parchment. Little Thomas drank it in—his tutors gushed over his knack for memorizing hymns and asking questions that stumped them, like “What is God?” It was a spark that wouldn’t quit.

By 14, war upended his cozy abbey life—Emperor Frederick II’s troops clashed with the Pope’s, and Monte Cassino became a battleground. Thomas fled to Naples, enrolling in the university there, a bustling hub of ideas where scholars swapped scrolls under orange trees. He stumbled across the Dominicans—ragged preachers in white habits, barefoot and fierce, preaching truth to the poor. Their passion grabbed him by the soul. In 1244, at 19, he ditched the family’s script and joined them, trading silk for sackcloth. His kin lost it—his brothers, hulking soldiers, ambushed him on a dusty road, dragged him to a tower, and locked him in for nearly two years. They tried everything: threats, bribes, even a woman slipped into his room to tempt him. Thomas snatched a burning log from the hearth, chased her out, and scorched a cross into the wall. “I’d rather burn for Christ than bow to gold,” he swore, his voice low but ironclad. His mother and sisters, worn down by his resolve, finally rigged a basket and lowered him to freedom—a breakout that set him loose for God.

The Silent Ox of Paris: A Nickname Forged in Quiet Might

In 1245, Thomas rolled into Paris, Europe’s intellectual furnace, to study under Albertus Magnus, a Dominican genius with a beard as wild as his ideas. Imagine him then: a bear of a man, broad-shouldered and heavy, with a mop of dark hair and a gaze that seemed to pierce the horizon. He didn’t chatter—classmates mocked him as the “Dumb Ox,” snickering at his bulk and his habit of sitting silent while they sparred over theology. He’d hunch over his desk, quill scratching, lost in thought as debates swirled around him. But Albert saw the ember glowing beneath. One day, Thomas unraveled a knotty argument with a few calm words, leaving the room stunned. Albert chuckled, his eyes twinkling, and roared: “You call him the Dumb Ox? This ox will bellow so loud the whole world will hear!” The nickname stuck, softened to “Silent Ox,” a title for a giant whose voice rumbled in stillness.

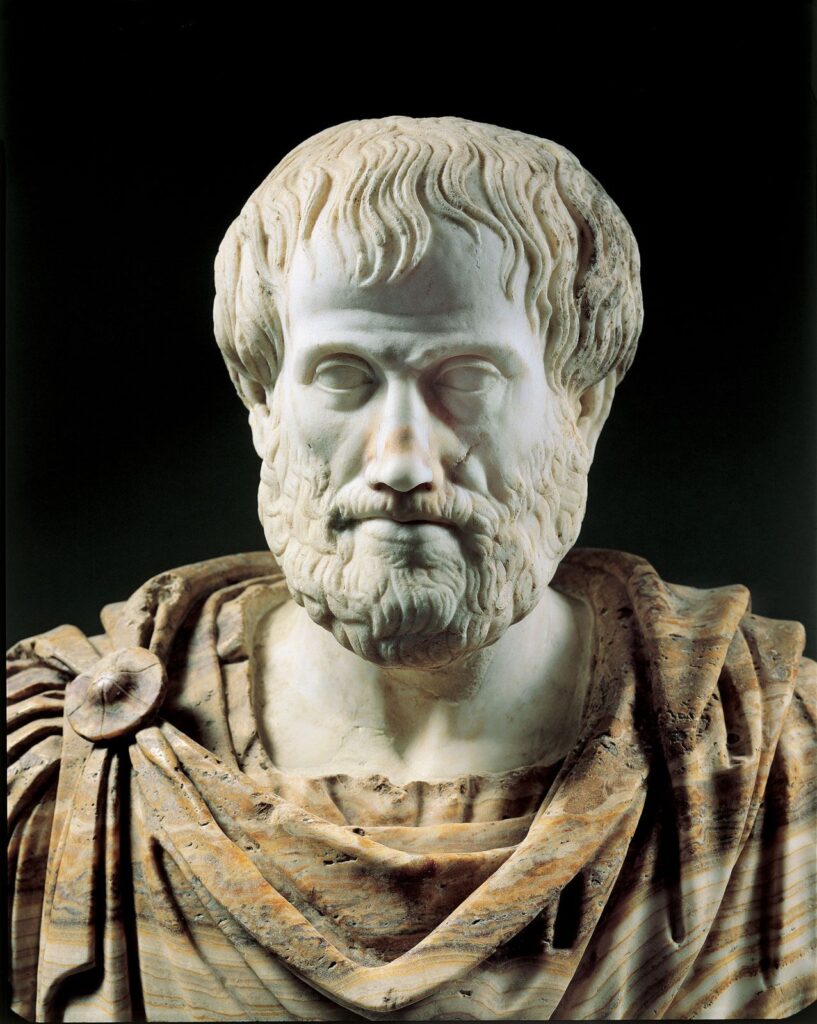

Paris was a cauldron of new ideas—Aristotle’s works, fresh from Arabic translations, were rattling the Church. Bishops fretted; his logic felt too grounded, too pagan. Thomas didn’t flinch—he trailed Albert to Cologne in 1248, lugging books and soaking up lessons like a sponge. He’d sit by the Rhine, watching barges drift, piecing together how reason could kneel to faith. By 1252, at 27, he was back in Paris, a master of theology, teaching with a quiet that hushed doubters. His early works, like De Ente et Essentia, hinted at his gift—tying Aristotle’s “being” to God’s essence, a whisper of the thunder to come.

The Aristotelian Alchemist: Turning Pagan Gold into Christian Light

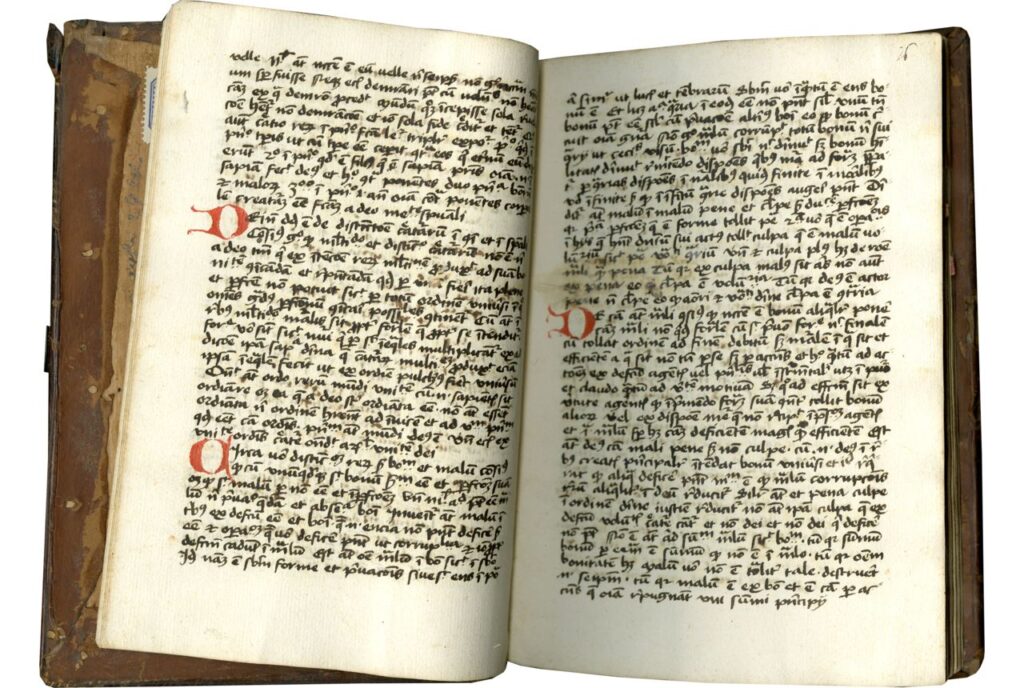

Thomas didn’t just skim Aristotle—he plunged in, wrestling the Greek’s dusty scrolls into the Church’s embrace, refining them like an alchemist turns lead to gold. Aristotle, dead since 322 B.C., had mapped reality through cause and effect—everything’s moved by something, everything’s got a purpose. His ideas, rediscovered via Muslim scholars like Avicenna, spooked clerics who feared they’d unravel Scripture. Thomas saw a treasure chest. In his Summa Theologica, begun in 1265, he cracked it open, pulling out Aristotle’s tools—substance, potency, act—and building a Christian tower atop them.

His “Five Ways” to prove God’s existence are pure Aristotelian muscle: motion needs a first mover, causes trace to an uncaused cause, possibility demands a necessary being, perfection points to a maximum, and design screams a designer. Aristotle stopped at a cold “Prime Mover”; Thomas baptized it, naming it God—alive, personal, infinite. He took Aristotle’s natural law—those innate rules wired into us—and lifted it into a divine blueprint, a moral spine for living right. “Reason is the ladder faith climbs to God,” he wrote, a line that flipped the script on faith as blind leap. His Summa Contra Gentiles tackled pagans and Jews, wielding Aristotle’s logic to prove truth isn’t faith’s rival but its wingman.

This wasn’t copying—it was elevation. Aristotle obsessed over the here-and-now; Thomas stretched it to eternity, threading grace through nature’s veins. He didn’t just use Aristotle’s categories—he crowned them with revelation, making ethics and metaphysics kneel to Christ. In the U.S., his natural law hums in courtrooms—think “self-evident truths” in the Declaration, a distant echo of his quill. He turned a pagan’s lens into a stained-glass window, letting divine light pour through.

The Master of the Summa: A Mind That Charted the Infinite

The Summa Theologica is Thomas’s colossus—over 3,000 articles, 2 million words, a sprawling map of God, humanity, and the cosmos. Started in 1265 as he shuttled between Paris, Rome, and Naples, it’s no ivory-tower tome—he wrote it for greenhorn friars, breaking down mysteries with a teacher’s heart. Picture him in a dim cell, quill racing across parchment, his big hands steady as he tackled “Does God exist?” or “Why suffering?” with a logic so crisp it’s a marvel. He’d pause, pray, then dive back in, stacking arguments like stones in a fortress.

He didn’t stop at the Summa. His hymns—Pange Lingua, Adoro Te Devote—still echo in churches, their verses dripping with awe for the Eucharist. He churned out commentaries on Aristotle, Scripture, and Boethius, piling up over 60 works. He taught in Dominican priories, debated heretics like the Cathars, and drew crowds with his quiet fire. By 1273, at 48, he was the Church’s north star—a brain so bright it dazzled kings and peasants alike.

The Vision That Hushed the Ox: A Glimpse Beyond the Veil

Then came December 6, 1273—a day that cracked Thomas wide open. He was celebrating Mass in Naples’ Dominican chapel, the air thick with incense, when the world fell away. Mid-consecration, he froze—his hands shook, his face lit up like he’d swallowed a star. He staggered out, silent, and slumped against a wall, staring into nothing. His scribe, Reginald of Piperno, found him hours later, pleading, “What happened, Master?” Thomas’s voice rasped: “I’ve seen things… compared to them, all I’ve written is straw.” “Everything I’ve done pales before God’s greatness,” he whispered, tears carving paths down his weathered cheeks.

What did he see? He wouldn’t spill—some say the Trinity blazing raw, others the Beatific Vision, God’s face unmasked in shattering glory. Whatever it was, it dwarfed his Summa, his decades of ink and sweat. He quit writing, leaving the Summa dangling mid-sentence on penance. Reginald begged him to finish; Thomas just smiled, soft as dawn: “My work’s done—the rest is God’s.” Three months later, on March 7, 1274, he died at 49 in Fossanova’s Cistercian abbey, felled by a fever after a donkey tumble en route to the Council of Lyon. That vision had already lifted him beyond the page.

The Doctor of Angels: A Legacy That Soars

Thomas didn’t fade—his light flared brighter. On July 18, 1323, Pope John XXII canonized him, proclaiming: “His teaching is a gift from God to the Church” (Bula, 1323). In 1567, he was crowned a Doctor of the Church—the “Angelic Doctor,” for a mind that danced with the divine. His feast, January 28, fills churches with his hymns, his words a balm for seekers. In the U.S., Jesuits and Dominicans hauled his ideas across the Atlantic, planting them in seminaries and colleges like Catholic University. The Founding Fathers sipped from his natural law—Jefferson’s “inalienable rights” owe a nod to Thomas’s moral spine.

He’s patron of students and theologians—his Summa a lifeline for bleary-eyed seminarians. In America, his faith-reason harmony sings to a culture torn between science and soul—think of classrooms dissecting his “Five Ways” or priests preaching his wisdom on Sunday. Pope Leo XIII, in 1879, hailed him as the Church’s lodestar, sparking a Thomistic revival that hums in philosophy departments today.

Lanterns of a Silent Soul: Thomas’s Life in Radiant Glows

Let’s wander through the lanterns Thomas hung along his path—each a flare from a silent ox whose bellow echoes still. His tale is a slow burn that lights the ages; here’s how it unfolded:

- Birth (1225): Born in Roccasecca, a noble with a restless spark.

- Dominican Vows (1244): Picked poverty over privilege, defying all.

- Paris Studies (1245): Sat under Albert, earning “Silent Ox.”

- Summa Begins (1265): Launched his titan work, reason kissing faith.

- Vision (December 6, 1273): Saw God, dubbed his words “straw.”

- Death (March 7, 1274): Passed at Fossanova, his flame eternal.

- Canonization (July 18, 1323): Sainted, a doctor for the ages.

- Crowed Doctor of the Church (1567): Pio V proclaims him the Angelic Doctor

I’m Jonathan Raeder, scholar of philosophy and the Catholic faith, deeply dedicated to exploring the teachings and traditions of the Church. Through years of study and reflection, I have gained a thorough understanding of Catholic philosophy, theology, and spirituality. My intention is to connect intellectual reflection with lived faith, shedding light on the richness of Catholic thought for all who wish to do so.